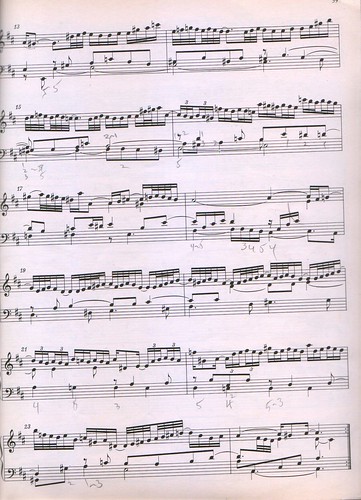

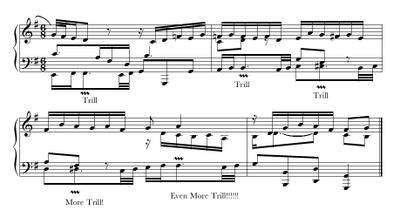

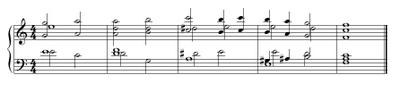

I love, by contrast, Bach's judiciously audacious use of octaves. For instance: the end of the 5th Partita. This fugal, complex gigue has a kind of manic insistence on not letting a moment go--and here's the counter subject, and here's the main subject, and here they are together, and no wait! don't rest! here it comes again in another voice! At some point an idea with a trill is introduced, and boy! do we get to know that one, and the piece comes to its climax with a sequence--a deliciously superfluous reiteration--of this quite-familiar trill, sequencing it wildly up the scale to the tonic... the kind of joyful obsession with this trill, we just can't stop trilling! not till we get there! (I can definitely see Bach smiling here, even grinning, holding a mug of coffee or a stein of beer while still somehow managing to play all the voices) ... and when he does get there (and this is "the point"): wonderful octaves in the bass, B, D, G... resolving to the tonic, once and for all, stopping the madness. Take that! (I could even imagine a kind of Miss Piggy karate chop):

That extra "display of strength" in the bass, its brusque simplicity of resolution, contrasts amusingly with all the intricate weavings, the chatterings, of what came before. The octaves are out of the frame of the piece, an intrusion: and yet only this alien element could bring us home. My former teacher, György Sebök, tried to instill in me something I probably have not yet totally learned (though nonetheless I think it is true): that endings in Bach do not say "I have finished the piece," do not declare any individual accomplishment, but rather indicate: "God wrote it, and it is good." Not especially religious myself, I nonetheless can hear this musical distinction, and sadly am often too caught up in my own sense of accomplishment, and desire for finality, at the end of a Partita, to let Bach's God speak.

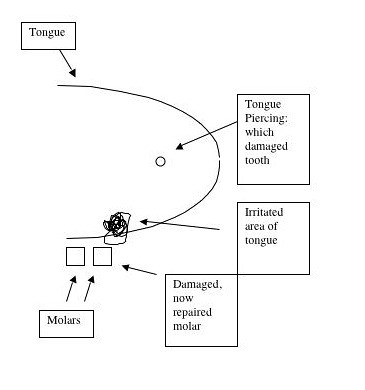

Returning to the Tchaikovsky passage, I got a wonderful suggestion from the concertmaster of the Lubbock Symphony, based on the premise of its motive of four descending notes. Any person acquainted with a reasonable percentage of popular culture could be expected to conflate this moment with "meow meow meow meow," and indeed it is pleasant to contemplate how different the piece would be (how much more feline!) if the pianist at that point broke into the Meow Mix jingle. I feel sure Tchaikovsky would have found some slightly long-winded way to develop those motives too. By an odd coincidence, the clarinetist of the Lubbock symphony is an old classmate of mine from Oberlin, and we reminisced over Texas white wine, while surveying the not-so-rolling nightscape of Lubbock, about how once we felt inspired to break into "Roll Out the Barrel" amid the last movement of Bartok's Contrasts--in studio class, no less. The professor, a man of considerable wry wit, compelled the audience to a stony silence, and we forced to pay for our prank with an awkward minute of nothing, no response, on stage... total humiliation.

All of which, I am sad to say, is by way of introduction (!) to my main point, but I can never recall being so exhausted by my lead-in as to contemplate breaking off entirely. Courage!

While I've been hard-pressed to find Bach in Tchaikovsky, Bach peeps out everywhere in Bartok's 3rd Concerto, assuaging this wigged-out junkie. Its first movement is full of gentle, playful, concerto-grosso-esque counterpoint: canons, inversions, dialogues, various "procedures" made tender and transcendent. (This constant back-and-forth makes it delicate, difficult to pull off, a real piece of concerto chamber music). But the second movement is a particularly extraordinary homage to the master, a re-framing: a "re-Bach-ification project."

It has basically three components:

a) What the strings play at the beginning: almost modal, a kind of pre-Bach counterpoint (like Palestrina?)... which leads to...

b) A chorale stated by the piano... a deliberate evocation of Bach chorales, "touched up" with harmonies from a more modern world... which leads to...

c) "Nature music": the hum of insects, bird calls, night sounds, breezes, falling and rising ripples... the absence of melody, per se ... simply sound, contour, time...

Now, each of these elements has its emotional baggage, its connotations, its "meaning"; but more importantly, so does the juxtaposition of these elements, the unabashed mixture of opposites (like "Meow Mix" in the Tchaikovsky concerto?). The different musics, passing from one to the other... The Bach chorale, with its more pungent, more "tonal," more directed, harmonies, and its more grammatical rhythm, is "born" out of the purer, more aimless, statements of the strings. The piano soloist, metaphorically, speaks the individual voice of experience (pain, loss, reaching) in response to some collective, earlier innocence. And though the piano is "more modern" than the strings, both are colored with a sense of being impossible styles: things that can no longer be written--past, lost, irrecoverable.

Bartok apes Bach, but not literally or systematically; he leaves traces of himself in the chorale: hints, signposts, reverberations. It is a chorale, reaching out to Bartok, sometimes becoming entirely Bartok, then reverting, returning, relinquishing.

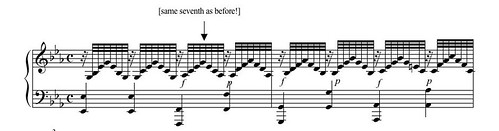

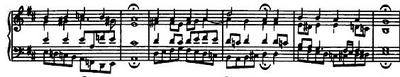

Let's take one phrase of the chorale, my sentimental favorite:

It reaches up, G to A, A to B, and when it lands on its climactic C... a twist. Instead of the E-natural one might expect, the C is harmonized with the note a half-step lower: D#. This D# is "not Bach," it is a painful mis-harmonization belonging entirely to Bartok's world... to his world so prominently peopled with tritones (A-D#)... and yet, and yet, can't one recall certain similar major-minor twists in Bach movements? But on the way down--how Bartok resolves away from this C--is the most clear, extraordinary, heartbreaking Bach homage. The treble descends: B, A, G; while the tenor voice ascends: G#, A#, B. Any music theorist worth his/her salt (not that I necessarily advise you spend a lot of time consulting music theorists) will tell you that this is called a "voice exchange," (B-G/G-B) time-honored procedure of four-part writing, of counterpoint in general... and FURTHERMORE that the chromatic alterations of some of the notes (G vs. G#, A vs. A#)... the sense that A "grinds" against A#, and G against G#, is called a cross-relation. Assume it has a name not just because it recurs so often, but because it has a special, beautiful effect.

To the internet! It took mere seconds on EveryNote.com to find the score of a Bach chorale with a similar cross-relation: you can't miss them, the chorales are peppered with them, those hidden, temporally displaced dissonances in the procession of concords. Here's the example I found:

At the end of this passage: In the alto voice, a descent, E through D-natural, C-natural, to B... in the bass, a corresponding ascent: C through C#, D, D#, to E. We are intended to hear the C and C# jangle, the D and D# conflict--then all is resolved. BUT THE SINGLE EXAMPLE DOESN'T MATTER! This is like a Bach "personality trait," a virtual calling-card of his chorale harmonizations, and when we hear it in the Bartok, we just know... this progression is achingly familiar, it taps into the musical/cultural memory, evoking Bach's ghost. It is one of the most beautiful idiosyncrasies of the chorales... a birthmark of the style.. and Bartok summons it obviously lovingly, like we summon to our minds the endearing oddities of an absent friend or love.

In the Bartok phrase, the A and A# are heard simultaneously, on the same "weak beat," as a passing tone; but the G# is heard on the first beat, while the dissonant G-natural is heard on the third (check the score again if you feel like it). We are meant to hear the dissonance displaced over time, and the displaced dissonance is no weaker than its simultaneous cousin... the memory of the previous note grinding against the new note we now hear. (Power of memory?) Yes, though the note is gone (though Bach is gone), it is still present, it affects events, must be understood... a cross-relation, a relation across time and across a musical interval, a deliberate paradox inserted in the counterpoint, two conflicting notes coexisting and resolving.

But what do you know? This G#-G-natural cross-relation--the juxtaposition of major and minor thirds--seems awfully similar to one of the most characteristic elements in Bartok's "native" harmonic style. (The layers of relation: first simply the G#-G-natural; then the way this relation evokes Bach; then the way this, in turn, draws comparison between Bach and Bartok.) Bartok's adaptations of Hungarian folk music pay special attention to the pungent, wonderful coexistence of major and minor thirds. Very often his cadences make no effort to decide, and simply splat down on both. Just a coincidence? No way. In the return of the chorale, Bartok makes this correspondence crystal clear; he insists on it, dwells on it, materializes it: the piano improvises at the end of this phrase in Hungarian style, repeatedly emphasizing the dissonant G-natural against the G# being held in the orchestra, like a folk lament gone virtuosic and wild:

Bartok has "discovered" a correspondence, a musical pun, a homonym, a common ancestor between himself and Bach... the cross-relation... this slow movement is its demonstration and revelation. The pianist, improvising counter-melodies to the chorale in its return, simply cannot help "expounding," making more steps in this direction, bringing Bach and Bartok together, reaching across the gulf. This juxtaposition of "opposites" is at once audacious and thrilling (hearing those Bartokian clusters superimposed on chorale cadences!) and, to my mind, often deeply sad and touching: dispossessed. A conversation from a distance, where neither party is entirely at home. Dissonances from two worlds, touching.

I haven't even touched on the most "dissonant" section, the middle section of movement, the "nature music." To my one remaining reader: we are in the home stretch.

After the opening section, where the piano says--with difficulty, by steps--what it has to say, the chorale gives way to a second form of innocence (not the strings' modal innocence), something outside the realm of music entirely, something once again collective. How can I account for the feeling that takes hold of me when, after the chorale's final cadence (tonal?), and the modality of a string interlude, I hear the Bartokian cluster of the middle section, the intrusion of modernity, leaping across centuries? A leap of faith. The way in which it is done is extraordinary: one doesn't hear a beat or a pitch to start the new section, but instead the "quantified" pitches of the opening section are replaced by a hazy, elusive tremolo. Suddenly we are lifted from musical "statements" into a world of pre-musical, musical being. We are hovering above music. The piano states a bird-call, injects the minimum of purpose and pulse into this soundscape...

If we think of the string music as evoking the beginnings of counterpoint, of musical artfulness and cultivation, and the piano chorale as a step further along, slightly more cultivated, the middle section is a paradox. While clearly modern, sophisticated, full of technique and developed craft, this craft is brought to bear to express something absolutely non-cultivated: pure nature. This slow movement can't decide whether to be cultivated or not; it is ambivalent, torn. It relies so heavily on memories of culture, on associations, on musical history, on nostalgia ... as we have seen... but also reaches out to non-culture, to the absence of culture.

But all this is academic-speak. I want to get in words, finally, this sense of joy at the junction, when Bach/Bartok chorales are "replaced" by bird-calls and breezes.

It is as though Bartok thought so deeply through the sentences of his chorale, its heavy, beautiful meanings ... but then thought suddenly that the world needed to be wider. The piano's chorale is self-sufficient but not enough. (Even Bach, the great master, is not enough.) When the soloist switches to the intermittent voice of a bird, away from the continuities of the chorale, I feel a tremendous elation, born of distance, of the impossibly strange traversed. Bartok's vision of nature here is so generous, tweaked with dissonance, but nonetheless entirely good: regret-less. Against which the cross-relation of man's chorale: so much painstaking, heartbreaking thought.