What I noticed (and what it was therefore too late to express) was a specific quirk of the organization of the variations. I have often felt impatient, at chamber music coachings and lessons, when the coach insisted on dealing at length with the timing of the transitions between variations. (No, wait a little longer here. Try to end this variation "up in the air," but more finality after the next one, etc.) It always seemed to me a bit of musical "bean counting," where one focused too much on the bread and not enough on the meat of the sandwich, so to speak. But yesterday, the joints were "all up in my face." There are several very odd connections, in which Beethoven seems to deliberately introduce a disjunction at the transfer... (at the moment when you would think he would want to "smooth things over") ... just as it seems when I walk from one car to another of the Amtrak train I am in now, the connectors between cars are bumpier, wobblier, and I am more likely to spill my decaf coffee on the way back from the cafe car. Not a very transcendent metaphor.

Between the first half of the theme, for instance, and the second, there is this one barren note, E. It is the only unison (unharmonized) note.

Now, I don't find the theme "sad" as a whole--its overall emotional state is wonderfully abstract--but the A minor to which this unison note leads is to my mind quite desolate. I am always struck, whether practicing, performing, or listening, at this moment: how unusual (how powerfully still) the A minor sounds, how perfectly it represents its own harmonic identity. If I am performing it, I often feel a kind of inner deflation, a call towards listening and reflection rather than playing and communication. It is deeply opposed to the raging, searching C minor of the first movement, it is not at all the same kind of minor: this A minor seems a kind of negative, exhausted mirror image--a sadness now past. These few bars of A minor are absorbed within the theme, like a bubble of minor floating in the major; each subsequent variation perpetuates this (essentially emotional) architecture, revisits the minor only to "reconvert" it to major. So, too, the moment of despair in the larger scheme of the movement, the chromatic wandering moment, the slippage, is absorbed in a larger transcendence and affirmation. I shouldn't say "despair" as Beethoven so carefully rides the line; the sadnesses in this movement are so beautiful that you cannot really get depressed about them. (Not everyone who is lost is sad.)

To return to this one unison note, E: I love it. It has its own color: dark, unmoored. It does not belong. The framework, the certainty of the previous C major is removed, but not absolutely. It is simply a pivot, the very minimum possible of transition: any more harmonic "explanation" would ruin it, would make the transition too obvious; its enigma is its meaning. Also: its short duration. It is like a vacant moment in the narrative (hollow is the word I keep coming around to in my head), a hiccup during which something is perceived.

At other junctions Beethoven introduces different kinds of hiccups. I have spent a lot of time trying to figure out how to "fit in" all the interesting voice-leading happening in the first two variations of this movement--particularly the voice-leading between halves. A lot happens. How can I give all this beautiful stuff its due, without slowing down, without losing proportion?

Let's take the first variation for an example. Things are going along fairly smoothly, according to a certain pattern of filling in the notes:

But towards the end of the first phrase the activity level jumps, the pattern is extrapolated, stretched: the chromaticism spikes. It is hard to put one's finger on it, but Beethoven introduces new, "unnecessary," complications at these cadences (A-flat, A-natural, B-flat, B-natural):

The music becomes thornier, harder to follow, a labyrinth of near-resolutions. It is as though something is building up, some excess of meaning, and Beethoven has to "cram it in" at the ends of the phrases, has to make things denser, more compressed, more fraught.

Interestingly, the transition to the A minor in the first variation is particularly fleshed out--"explained"--here a whole series of chords "stands in" for the one enigmatic E.

Precisely where the theme said the LEAST, this first variation says MOST. Beethoven is thinking end-heavy; the piece is tending towards profusion (not simplicity) in general, or at least towards an uneasy truce between profusion and simplicity, and these halves of the variations, in microcosm, tend to mirror this macrocosmic crescendo of activity.

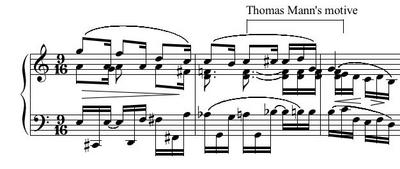

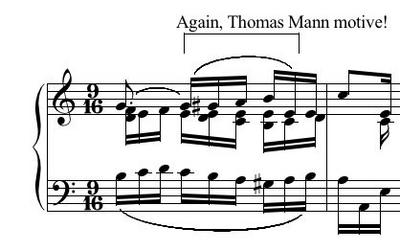

Thomas Mann, in Doctor Faustus, has a wonderful passage about Beethoven Op. 111 and he focuses on something I had hardly noticed... he concentrates on a C C# D G at the end of the movement, and the emotional importance of the introduction of the C# passing tone: which, in music theory speak, might be referred to as ... the lingering on, and complication of, the cadence.

But when it does end, and in the very act of ending, there comes--after all this fury, tenacity, obsessiveness, and extravagance--something fully unexpected and touching in its very mildness and kindness. After all its ordeals, the motif, this D-G-G, undergoes a gentle transformation. As it takes its farewell and becomes in and of itself a farewell... it experiences a little melodic enhancement. After an initial C, it takes on a C-sharp before the D ... and this added C-sharp is the most touching, comforting, poignantly forgiving act in the world. It is like a painfully loving caress of the hair, the cheek--a silent, deep gaze in the eyes for one last time. It blesses its object ... with overwhelming humanization...

Mann's effusion gives me some comfort, some assurance that I am not the only one out there waxing perhaps over-poetical at times... But as the musical examples above show, this C-C#-D is not a new event at the end of the piece... these little, complicated, transitions at the end of the theme halves that I have been obsessing about, these disjunct moments of crammed meaning, are intended to introduce and develop that very motive, that "most poignantly forgiving act in the world." (Did Mann make a mistake? Not look hard enough? Or did he not care?)

The "reason" why Beethoven fills out that simple E (destroys its simplicity) is to readdress this melodic idea... essentially the creation of a new mini-theme, a new object of concern, a "theme of variation." Something that happens, interestingly, only at the ENDINGS. The theme is somehow "not enough," somehow does not stand on its own... unlike in Op. 109 where the theme, in all its simplicity, proves to be plenty, and is reiterated at the piece's conclusion. Op. 111 dissolves into profusion, fragments, second thoughts.

This commentary on the theme becomes like a cameo role that steals the show. As I was playing yesterday I began to feel this second entity, its eruption at the ends of the phrases, its emergence as a competing, asymmetrical force. And I wanted to feel it much, much, more. I wanted to rewrite the piece in my head, so to speak, giving this cameo its true, central role. It was too late of course for that particular concert, but how could I regret my illumination?

Another hiccup I found irresistible yesterday as I was playing the Sonata through was the little soft half-measure at the end of the second variation, before the forte explosion of the third ("jazzy") variation:

There it is: a tiny expression of the dominant between tonics. Beethoven insists on creating another registral space (bass-free, "inessential") for this essential chord; he makes the transition parenthetical, a non-event. (Just business.) Partly this allows the new variation to explode into being, rather than to simply occur... it complicates the transition quite a bit, like a musical "double-take," (it's loud, no it's soft, no it's loud again; it's tonic, it's dominant, no, it's tonic again!): a little flurry of activity, compressed switching of mood, register, etc... I felt yesterday as I played it that I had not yet found the right joy for that moment, the right twinkle in Beethoven's eye, and it is hard, because it goes by so quickly that, like a rural town, if you blink (or if someone in the audience coughs) you'll miss it, and yet I had the feeling as in the other transitions that it was essential, that a lot of meaning lay there in the elusive nanosecond. Many musical moments are more important than their duration would suggest.

The gradual emergence of wit from this transcendent movement is one of its most fascinating (bizarre, unexplainable) elements; yesterday as I played it, I began to feel the evil urge to let its silliness loose (sacrilege, the elephant in the china shop) but I think it lovely that Beethoven managed to sweep that aspect of the cosmos in too; the first movement has not a silly bone in its body, and the overall message of the second movement is not silly either, to say the least; but in decorating this theme, some element of the outrageous, the unassimilated, the ridiculous, creeps in and Beethoven did not, like some too-serious artists, want to let that part of existence go.

The bumps at the connections, the omission or cramming in of meaning at the ends of things; in his supreme control over materials, obviously a conscious desire not to be too smooth. "Slick" is the dangerous thing that smooth leads to; it lurks at the bottom of smooth's slippery slope. Not slick at all, this Arietta; my urge to be a "great interpreter" and sweep all the notes together in one vast arc is counteracted by Beethoven's interspersion of craggy details; and I have the feeling Beethoven wants me to continually cross-refer, from macro to micro, to constantly wonder why certain things happen, what principles they manifest, and to struggle to fit everything in, and to always feel, as I do when packing my suitcase or contemplating my schemes for life or trying to understand another person, that something, some stubborn strange something, has been left out.

5 comments:

I wonder what Freud might have to say about such a detailed analysis of #111? :)

More seriously, as a listener and but not as a performer, this piece has been troublesome for me.

On the one hand, classical music fans are culturally acclimated to bend on one knee at the merest mention of Opus One-Eleven. Yet I recall driving home one evening a year or so ago, and hearing "a long piano piece" on the FM radio. Not being a pianist, I did not have the slightest clue of what it was. I simply knew that I wished to Heaven that it would end soon, it seemed to drag on and on and never get into a true "fireworks finale" mode. In due course, the announcer came on and said "that was Daniel Barenboim, performing the Op. 111 of Beethoven." [segue to commercial].

That incident troubled me, and still does. If I'd known the identity of the piece in advance, I suspect I would have been prejudiced in its favor. But as a complete blind test, I was thoroughly underwhelmed.

Some have suggested that it was Barenboim, and not Beethoven, against whom I was reacting. Maybe. But still an interesting case-study of sorts.

BTW, I've listened to classical music for many years, mainly chamber music and string music. So it isn't like I am a novice to the genre. But I am a very far cry from a scholar-specialist in keyboard literature!

heavy, light, and dark

At some risk of reading too much biography into the music, I sometimes feel Beethoven draws attention beyond (or within) the audible to something else. This really struck me for the first time while I was in an orchestra performing the violin concerto. Being rather underutilized during the slow movement, my mind wandered--but attentively. I had degenerated into listening, so much so I was concentrating on the faint patter of rain somewhere overhead, on the roof of Sanders Theater. Like the birds in the slow movement of the 6th Symphony--which still annoy me as too literal to be musical--the rain wasn't supposed to be heard as a thing itself but as an indicator of how much else had been screened out. Or so I would like to imagine Beethoven's intentions.

The connection to Op. 111 Arietta is that I consider it an example of how the audible eventually borders on silence, where elaboraton becomes almost indistinguishable from attenuation. The resimplification at the end of the movement, with its subtle inflection, doesn't feel like an obligatory return. It's more like the sound left behind after the music has moved on, somehwere out of earshot.

The Op. 111 is a piece that I avoid out of reverence, maybe afraid it could be trivialized by overexposure, or my lack of attentiveness. But one time I did put on a recording (by Alfred Brendel) was 30 years ago, after I had come home from watching a Red Sox game one night at Fenway Park. No sooner did Brendel get to the end of the second movement than the lights went out--all over the neighborhood. The outage lasted little more than 10 minutes. The next I had almost forgotten about it when I was riding home on a bus. Then I overheard a passenger from my neighborhood haranguing the bus driver. She had missed a bus earlier that day even though she was on time. She was convinced the bus had come too soon. Since her house and her clocks must have been affected by the outage, I thought for a moment could explain to her what happened after the Red Sox game and Op. 111.

32 by Pollini in my "Classical" top five. Beethoven's last and the greatest...

And you are my hero!

Mr Denk: a wonderful piece of writing. Just as were the performances by you that I've had the pleasure of reviewing (including a transcendental "Kreutzer" with Soovin Kim).

You may like a comment made on the radio almost half a century ago by Edward Sackville-West. He described the end of Opus 111 as "depositing us gently on the edge of eternity."

Best wishes,

Bernard Jacobson

PS Forgive me if all this is in a very unbloglike format - first time I've ever participated in communications of this kind.

dissect, pick over, analyze, put under a microscope, subject to chromatography-that's all good-- bottom line-- it is perfect as it was put together by LVB.

Not "too many notes"; not too few; not incongruous; just right.Accept the genius; can bring you to tears.

Post a Comment