Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Update

Vis a vis the "torment" mentioned at the end of the last post: after a massage, a long shower, some more aloe cream, a short walk, a thin crust pizza with prosciutto and mountains of arugula, a cup of mango and coconut gelato, and a short dip in the pool, my torment seems to have abated somewhat. Concert? What concert?

Monday, February 27, 2006

Pleasures

Basking in the breeze, awaiting my chimichurri, I paused to contemplate my complicated relationship to pleasure. A recurring motif of this blog is certainly the tug between my artyfarty tendencies (the "real Jeremy"?) and my evil twin who wishes for nothing more than to be a skateboarder or a surfer, or some such bumlike person, living idly in fair climes off a trust fund while meticulously scheduling my irrelevancies according to whim. More than several such persons, I am guessing, wander the streets here in South Beach. I love the sun and the sand, and even just the idea of a frozen drink, frozen perhaps just in the moment of my reaching for it, on a hot day, from my wicker chair... in the moment before it can be tasted, and limited by reality.

The young, sickly Proust is told by a family friend that though he cannot travel he at least has "the life of the mind," which is the best life, and the young sickly Proust is quite nonplussed. My heart aches with his at that moment. The limitless, boggling brain suddenly seems a very small room encased in a skull. Proust eventually does travel, and then the most miraculous, beautiful things happen (even though they are nothing more than "the usual" travel incidents); his processes of metaphor and association move and flow then like the train or boat he is aboard. It is still, to be sure, the life of the mind, but the mind's doors are open and the breeze is blowing in.

It is interesting to contrast the sensualism of making music onstage every evening for crowds massed in the dark, and the sensualism of a sunny afternoon walking alone around South Beach. Onstage, I am supposed to communicate, give off, radiate out; even the lighting conspires in this metaphor; but walking down the street here, I feel it all the other direction, coming into, at me; I can be no significant source of sensualism in this pleasure-dome; it, the sun, the place, the mode of living, coats me in its excess. I am the dark audience for this lit spectacle. I love these solitary walks through Xanadu, but there is also a hint of antagonism in the relationship, a sense that my presence there is tolerated only provisionally. I am an impostor on the beach, but also perhaps at the concert hall; how can someone so attracted to the pleasures of the flesh be at home in the stuffy Classical Music world?

Perfectly and painfully encapsulating in reality this conundrum, today I am punished for yesterday's pleasure with a significant amount of sunburn, which could have been avoided so easily. I have tried to atone by spending spectacular amounts of money on aloe lotions. It is clear to one and all from my vivid face that I am a beach novice who fell into the stupidest of traps, and so this morning I put on my Johann Sebastian Bach T-shirt as a way of explaining. "You see, everybody, I'm really a classical musician and I think about Bach a lot and that's why I forgot to put on sunscreen." Perhaps though people won't read so deeply into the shirt as I imagine, and they will just see a sunburned fool.

This fool cannot go out on the beach today, but can only watch the surfers from his room, with the plasma TV on mute, where a preacher explains more or less that loving God will make you rich (he never got around to that "eye of the needle" bit), and Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier spread out on the desk. Luckily JS reminds me that the contradiction of flesh and mind I have been feeling is moot. Reaching for the aloe cream, I look at those black scratchings on the page, and I feel like there is no wall, no division, no audience or performer; just revelation; the music seems animated to me, like blood rushing through my veins... so touching, so immediate, even if it is centuries distant ... this beautiful intervention convinces me that if Miami seems to exacerbate a certain torment of my inner sensualist, perhaps it is just the torment I need in order to be me.

The young, sickly Proust is told by a family friend that though he cannot travel he at least has "the life of the mind," which is the best life, and the young sickly Proust is quite nonplussed. My heart aches with his at that moment. The limitless, boggling brain suddenly seems a very small room encased in a skull. Proust eventually does travel, and then the most miraculous, beautiful things happen (even though they are nothing more than "the usual" travel incidents); his processes of metaphor and association move and flow then like the train or boat he is aboard. It is still, to be sure, the life of the mind, but the mind's doors are open and the breeze is blowing in.

It is interesting to contrast the sensualism of making music onstage every evening for crowds massed in the dark, and the sensualism of a sunny afternoon walking alone around South Beach. Onstage, I am supposed to communicate, give off, radiate out; even the lighting conspires in this metaphor; but walking down the street here, I feel it all the other direction, coming into, at me; I can be no significant source of sensualism in this pleasure-dome; it, the sun, the place, the mode of living, coats me in its excess. I am the dark audience for this lit spectacle. I love these solitary walks through Xanadu, but there is also a hint of antagonism in the relationship, a sense that my presence there is tolerated only provisionally. I am an impostor on the beach, but also perhaps at the concert hall; how can someone so attracted to the pleasures of the flesh be at home in the stuffy Classical Music world?

Perfectly and painfully encapsulating in reality this conundrum, today I am punished for yesterday's pleasure with a significant amount of sunburn, which could have been avoided so easily. I have tried to atone by spending spectacular amounts of money on aloe lotions. It is clear to one and all from my vivid face that I am a beach novice who fell into the stupidest of traps, and so this morning I put on my Johann Sebastian Bach T-shirt as a way of explaining. "You see, everybody, I'm really a classical musician and I think about Bach a lot and that's why I forgot to put on sunscreen." Perhaps though people won't read so deeply into the shirt as I imagine, and they will just see a sunburned fool.

This fool cannot go out on the beach today, but can only watch the surfers from his room, with the plasma TV on mute, where a preacher explains more or less that loving God will make you rich (he never got around to that "eye of the needle" bit), and Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier spread out on the desk. Luckily JS reminds me that the contradiction of flesh and mind I have been feeling is moot. Reaching for the aloe cream, I look at those black scratchings on the page, and I feel like there is no wall, no division, no audience or performer; just revelation; the music seems animated to me, like blood rushing through my veins... so touching, so immediate, even if it is centuries distant ... this beautiful intervention convinces me that if Miami seems to exacerbate a certain torment of my inner sensualist, perhaps it is just the torment I need in order to be me.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

I Have A Question

Are dumplings the answer? Yesterday, a steaming circle of them looked like a bundle of immaculate food-children dropped by a divine stork: fecund, promising, chaste. To mar their whiteness with black soy sauce was a necessary, beautiful sin. I curse today limitations on the parameters of questions and answers, their too-easy, too-obvious pairing... i.e.:

Are you hungry? Eat something.

Are you tired? Get some sleep.

What would you like to drink with those nachos? A margarita.

Yes, these catechisms seem timeless and indisputable. But I submit that answers often jump ship and interpose themselves on questions to which they do not belong. For instance I did not eat the dumplings; they were not an answer to my hunger, which was solved by spicy soup; but they seemed an answer to another question: something having to do with relaxation, the comforts of lunchtime, of workday routines which are not oriented towards evening concerts, but which revolve around more predictable effort, into which steaming dumplings may come as a soothing relief... it may sound ridiculous to say that when I saw the dumplings (I did not need to eat them, only see them) they relieved me internally and made me cherish my nook for the moment, in time and in space. I was the satisfied filling of a dumpling. I felt like someone settling down to a good old-fashioned novel, or squishing into the perfect armchair by the fire for a conversation that does not promise to be usual or tiresome. And also yesterday evening, when a chilled bottle of white wine approached the table, and four of us were arranged around its square with our waiting glasses, I felt it was an answer, not to thirst or stress or food, but to some larger question of ritual and companionship...

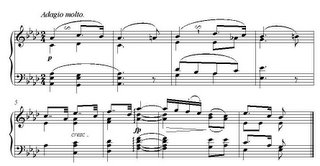

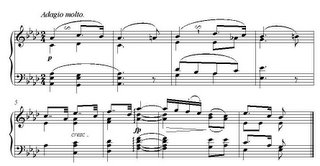

At the opening of the "Kreutzer" Sonata, I sit idly but reverently by while the violin poses a very beautiful and difficult question (difficult to play, difficult to answer). It is a major-key question, filled with consonances (thirds, octaves, sixths, fifths), and trailing off.

The last note (the resolution) is short; after the breadth and lyricism of the idea, it gives itself over abruptly to silence. I think this is one of those unusual, extraordinary beginnings that distinguishes itself from the greater mass of classical openings not through any outrageous harmonic maneuver, ambiguity, or daring, but through the audacity of its sudden, naked Appearance: the Idea itself, presented whole (immaculate conception). It does not ask the typical questions of "famous" openings, such as What Key Am I In? or Where's the Downbeat? or What's the Tempo? or so forth (all more or less rephrasings of the common life question Where Am I Going?); all those questions are dismissed as unimportant (the neurotic concerns of other pieces), as the initial Idea speaks, presents to us its "grain" (like that of a piece of wood). A lot of times listening to the beginnings of classical pieces, I can say to myself: yes, this opening idea comes from the tonic triad, and this is the coy reply moving us to the dominant, etc. etc ... in these cases the opening ideas, the premises, their questions and answers, derive from the familiar and common, and allow us to experience the music gradually, as an unfolding of "logic": drapery on the scaffolding of tonality. Not as a shock of identity. I have a hard time seeing where the opening of the Kreutzer "comes from." There are no easy sources for its particular beauty. The sort of question I feel it asks is Why Do I Exist? or How Did I Come Into Being? And that is what gives it, for me, a kind of surreal beauty: an oddly certain question, a fragment that is strangely and prematurely complete. The piece is mature beyond its measures.

[Regular readers of Think Denk are not deluding themselves if they imagine, or anticipate with sinking certainty and dread, that I am drawing some implicit comparison between the opening of the Kreutzer Sonata and a steaming plate of dumplings; BUT do they suspect I am willing to sink yet sillier and imagine the ensuing piano phrase as soy sauce? This may yet have been left to the imagination; too late, now. I am sorry.]

After a half bar of silence... a silence that might be interpreted "how do I respond to that?" ... the piano finds something to say: what appears to be the same idea, but from its second note shifting dramatically into the minor key.

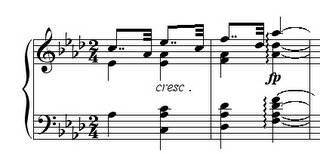

After the shock of this, one can come to an understanding: Beethoven is setting up a dualism of light/dark. The violin idea, unmarred by accidentals, seems to represent light, pure A major; whereas the pianist wanders into a darker place, the shadowy antithesis. But interestingly, the pianist's phrase, for all its dark F-naturals, concludes on a luminous G major chord (with a beautiful F-sharp suspension!)... it cannot decide whether to be night or day. I sense four separate moments of shock in the piano's opening statement: 1) the pianist's first note, the opening forte/piano, breaking the silence; 2) the pianist's second note (shifting unexpectedly to minor); 3) the downbeat of the pianist's third bar, with the deceptive bass motion up a half-step; and 4) the G major "arrival" (subito piano... a beauty, a sweetness, which was not anticipated). Such a density of surprise is hard to absorb; I realize, that for the "average" concertgoer, it may not even exist; but I think it is there. At one level, one perceives a very simple light/dark antithesis, but at another, events present a much more complicated question/answer in which the nature and identity of the essential dualism is in doubt.

From the outset, the piano is not an original thinker; it (he/she) is repeating, rethinking, reassessing... derivative, complex, living in a world already created by the hand of the violinist. (Pianist as original sin? curse of knowledge?) As events unfold, the violinist and pianist together undergo the darkest, most searing moment of the introduction--a moment which basically repeats the bass motion, and thus the essential "meaning" of the pianist's opening statement--

And they, too, together come to realize that fragile G major is the precarious answer. How can G major be an answer, in the key of A major? Through the obvious expedient of two rising fourths, A-D, D-G, (or two descending fifths) Beethoven arrives impossibly far afield. This, too, I think the "average" hypothetical median concertgoer (who does not really exist) does not always perceive. Sometimes, while I am playing the piece, and when we get to that moment, and someone coughs a bored cough right then, in the shocked, supreme, post-G-major silence, I want to get up from the piano and explain to them how incredibly amazing it is that Beethoven takes us there, how he tries to rock our world and propose that 2+2=3. It is like that scene in Ocean's Twelve where Clooney and co. want to rob a house in Amsterdam and the window is a foot too low for their scheme, and so they decide to dive underwater and raise the entire building up a foot using winches or something. That's how weird and wild it is to move from tonic A major to G major (flat seven!!!!!!); imagine the two root position chords next to each other, all the parallel fifths and octaves; all the rules and taboos that are broken to be there. I would deliver this little speech and people would be weeping for amazement, fainting for pleasure, and paralyzed by the marvel of Beethoven's audacity; one small sob would break out from the back of the house, and be reluctantly muffled; and then we would sit back down and play on. Haha.

For G major is the "wrong" answer to A major; it fits in no nacho/margarita category of the obvious. Its answeritude (answer+attitude=the quality of being an answer) comes from another source; it is more of a spiritual, metaphorical answer (light passing through dark to get to another, different light), which of course spins around on itself and becomes the question. I cannot help juxtaposing the strangeness of this answer against the circularity and precocious completeness of the violin's first statement; what kind of world is it where the opening idea can be so serene, beautiful and extraordinary, so insular and perfect; and then the harmonic basis can tectonically shift down a radical whole-step? A world where dumplings don't have to be eaten to be savored, where questions and answers are like free radicals, bonding with unexpected mates.

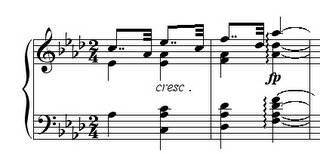

Towards the end of the first movement, after all our storm and stress, there is another wonderful, disturbing nexus of questions and answers. The violin proposes a cadence in B-flat major (impossible), in Adagio:

Every night at the piano I offer up a little prayer of thanks to my bassline of that moment, sinking that unthinkable fifth from F to B-flat. As always, V goes to I; the cliché spawns the revolution. A revolution because the "grain" of B-flat grates deeply against the prevailing A minor... literally and metaphorically. The moment is temporally distended; we are forced to sit and listen to the impossible. As in so many Beethoven angry minor-key movements, the metaphor of the island of calm is engaged; little patches, oases of lyricism, scattered throughout the movement (the second theme, for instance), call to each other structurally across stormy expanses ... and this is the crucial last one, farewell and summary, the violin's last halt to the movement's urge of relentless motion, so unutterably beautiful, expressing so much in the concision of its three chorale-like notes, distilling the idea again back to its essence... saying "stop, wait." To which the piano responds fatefully, without speeding up, twisting the harmony with the same three notes:

Although the rhythm is still stopped, though we are yet suspended in the standstill (marvelling, waiting), the harmonies have wended their way back to A minor, which means we know with that sinking feeling that we are back in the tragic world of the movement's overall gesture. The piano is again "too complicated," it answers with mixed messages; we are stopped, but wary; we know that an outburst is coming (we fear it)... there is a realization but it is fatal. I will never play to my satisfaction those last two Adagio chords; the connection between them has to express so much (falling, relinquishing, inevitability, despair).

And then the outburst happens ... the movement crashes to an end... The audience seems always to get caught up in this moment, to want to applaud; I too am thrilled and often feel demonically possessed by this ending, by our scales and ferocious concluding chords, dominant/tonic. But something about this last answer always seems misplaced. Its fury cannot possibly "answer" or resolve the pathos of those two preceding Adagios; there is no balancing, no summing up, what has occurred: there is too much. It is like a person in denial, a person who still thinks one question has one answer, and rages impotently against multivalence. Wow, how did I get there from dumplings? Perhaps via Beethoven.

Are you hungry? Eat something.

Are you tired? Get some sleep.

What would you like to drink with those nachos? A margarita.

Yes, these catechisms seem timeless and indisputable. But I submit that answers often jump ship and interpose themselves on questions to which they do not belong. For instance I did not eat the dumplings; they were not an answer to my hunger, which was solved by spicy soup; but they seemed an answer to another question: something having to do with relaxation, the comforts of lunchtime, of workday routines which are not oriented towards evening concerts, but which revolve around more predictable effort, into which steaming dumplings may come as a soothing relief... it may sound ridiculous to say that when I saw the dumplings (I did not need to eat them, only see them) they relieved me internally and made me cherish my nook for the moment, in time and in space. I was the satisfied filling of a dumpling. I felt like someone settling down to a good old-fashioned novel, or squishing into the perfect armchair by the fire for a conversation that does not promise to be usual or tiresome. And also yesterday evening, when a chilled bottle of white wine approached the table, and four of us were arranged around its square with our waiting glasses, I felt it was an answer, not to thirst or stress or food, but to some larger question of ritual and companionship...

At the opening of the "Kreutzer" Sonata, I sit idly but reverently by while the violin poses a very beautiful and difficult question (difficult to play, difficult to answer). It is a major-key question, filled with consonances (thirds, octaves, sixths, fifths), and trailing off.

The last note (the resolution) is short; after the breadth and lyricism of the idea, it gives itself over abruptly to silence. I think this is one of those unusual, extraordinary beginnings that distinguishes itself from the greater mass of classical openings not through any outrageous harmonic maneuver, ambiguity, or daring, but through the audacity of its sudden, naked Appearance: the Idea itself, presented whole (immaculate conception). It does not ask the typical questions of "famous" openings, such as What Key Am I In? or Where's the Downbeat? or What's the Tempo? or so forth (all more or less rephrasings of the common life question Where Am I Going?); all those questions are dismissed as unimportant (the neurotic concerns of other pieces), as the initial Idea speaks, presents to us its "grain" (like that of a piece of wood). A lot of times listening to the beginnings of classical pieces, I can say to myself: yes, this opening idea comes from the tonic triad, and this is the coy reply moving us to the dominant, etc. etc ... in these cases the opening ideas, the premises, their questions and answers, derive from the familiar and common, and allow us to experience the music gradually, as an unfolding of "logic": drapery on the scaffolding of tonality. Not as a shock of identity. I have a hard time seeing where the opening of the Kreutzer "comes from." There are no easy sources for its particular beauty. The sort of question I feel it asks is Why Do I Exist? or How Did I Come Into Being? And that is what gives it, for me, a kind of surreal beauty: an oddly certain question, a fragment that is strangely and prematurely complete. The piece is mature beyond its measures.

[Regular readers of Think Denk are not deluding themselves if they imagine, or anticipate with sinking certainty and dread, that I am drawing some implicit comparison between the opening of the Kreutzer Sonata and a steaming plate of dumplings; BUT do they suspect I am willing to sink yet sillier and imagine the ensuing piano phrase as soy sauce? This may yet have been left to the imagination; too late, now. I am sorry.]

After a half bar of silence... a silence that might be interpreted "how do I respond to that?" ... the piano finds something to say: what appears to be the same idea, but from its second note shifting dramatically into the minor key.

After the shock of this, one can come to an understanding: Beethoven is setting up a dualism of light/dark. The violin idea, unmarred by accidentals, seems to represent light, pure A major; whereas the pianist wanders into a darker place, the shadowy antithesis. But interestingly, the pianist's phrase, for all its dark F-naturals, concludes on a luminous G major chord (with a beautiful F-sharp suspension!)... it cannot decide whether to be night or day. I sense four separate moments of shock in the piano's opening statement: 1) the pianist's first note, the opening forte/piano, breaking the silence; 2) the pianist's second note (shifting unexpectedly to minor); 3) the downbeat of the pianist's third bar, with the deceptive bass motion up a half-step; and 4) the G major "arrival" (subito piano... a beauty, a sweetness, which was not anticipated). Such a density of surprise is hard to absorb; I realize, that for the "average" concertgoer, it may not even exist; but I think it is there. At one level, one perceives a very simple light/dark antithesis, but at another, events present a much more complicated question/answer in which the nature and identity of the essential dualism is in doubt.

From the outset, the piano is not an original thinker; it (he/she) is repeating, rethinking, reassessing... derivative, complex, living in a world already created by the hand of the violinist. (Pianist as original sin? curse of knowledge?) As events unfold, the violinist and pianist together undergo the darkest, most searing moment of the introduction--a moment which basically repeats the bass motion, and thus the essential "meaning" of the pianist's opening statement--

And they, too, together come to realize that fragile G major is the precarious answer. How can G major be an answer, in the key of A major? Through the obvious expedient of two rising fourths, A-D, D-G, (or two descending fifths) Beethoven arrives impossibly far afield. This, too, I think the "average" hypothetical median concertgoer (who does not really exist) does not always perceive. Sometimes, while I am playing the piece, and when we get to that moment, and someone coughs a bored cough right then, in the shocked, supreme, post-G-major silence, I want to get up from the piano and explain to them how incredibly amazing it is that Beethoven takes us there, how he tries to rock our world and propose that 2+2=3. It is like that scene in Ocean's Twelve where Clooney and co. want to rob a house in Amsterdam and the window is a foot too low for their scheme, and so they decide to dive underwater and raise the entire building up a foot using winches or something. That's how weird and wild it is to move from tonic A major to G major (flat seven!!!!!!); imagine the two root position chords next to each other, all the parallel fifths and octaves; all the rules and taboos that are broken to be there. I would deliver this little speech and people would be weeping for amazement, fainting for pleasure, and paralyzed by the marvel of Beethoven's audacity; one small sob would break out from the back of the house, and be reluctantly muffled; and then we would sit back down and play on. Haha.

For G major is the "wrong" answer to A major; it fits in no nacho/margarita category of the obvious. Its answeritude (answer+attitude=the quality of being an answer) comes from another source; it is more of a spiritual, metaphorical answer (light passing through dark to get to another, different light), which of course spins around on itself and becomes the question. I cannot help juxtaposing the strangeness of this answer against the circularity and precocious completeness of the violin's first statement; what kind of world is it where the opening idea can be so serene, beautiful and extraordinary, so insular and perfect; and then the harmonic basis can tectonically shift down a radical whole-step? A world where dumplings don't have to be eaten to be savored, where questions and answers are like free radicals, bonding with unexpected mates.

Towards the end of the first movement, after all our storm and stress, there is another wonderful, disturbing nexus of questions and answers. The violin proposes a cadence in B-flat major (impossible), in Adagio:

Every night at the piano I offer up a little prayer of thanks to my bassline of that moment, sinking that unthinkable fifth from F to B-flat. As always, V goes to I; the cliché spawns the revolution. A revolution because the "grain" of B-flat grates deeply against the prevailing A minor... literally and metaphorically. The moment is temporally distended; we are forced to sit and listen to the impossible. As in so many Beethoven angry minor-key movements, the metaphor of the island of calm is engaged; little patches, oases of lyricism, scattered throughout the movement (the second theme, for instance), call to each other structurally across stormy expanses ... and this is the crucial last one, farewell and summary, the violin's last halt to the movement's urge of relentless motion, so unutterably beautiful, expressing so much in the concision of its three chorale-like notes, distilling the idea again back to its essence... saying "stop, wait." To which the piano responds fatefully, without speeding up, twisting the harmony with the same three notes:

Although the rhythm is still stopped, though we are yet suspended in the standstill (marvelling, waiting), the harmonies have wended their way back to A minor, which means we know with that sinking feeling that we are back in the tragic world of the movement's overall gesture. The piano is again "too complicated," it answers with mixed messages; we are stopped, but wary; we know that an outburst is coming (we fear it)... there is a realization but it is fatal. I will never play to my satisfaction those last two Adagio chords; the connection between them has to express so much (falling, relinquishing, inevitability, despair).

And then the outburst happens ... the movement crashes to an end... The audience seems always to get caught up in this moment, to want to applaud; I too am thrilled and often feel demonically possessed by this ending, by our scales and ferocious concluding chords, dominant/tonic. But something about this last answer always seems misplaced. Its fury cannot possibly "answer" or resolve the pathos of those two preceding Adagios; there is no balancing, no summing up, what has occurred: there is too much. It is like a person in denial, a person who still thinks one question has one answer, and rages impotently against multivalence. Wow, how did I get there from dumplings? Perhaps via Beethoven.

Friday, February 17, 2006

Back

"Time to wake up, my fine moron friends." Cars were stopped ahead at the corner of 97th and Park, despite a green light, and the driver, through this remark, and some gentle beeping, reminded them of this paradox. Ahh, the gentle northeast, which I rhapsodized yesterday on this very site!

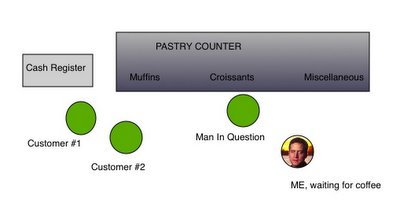

From the very first SECONDS of rearriving in the Homeland (a word now inextricably linked, sadly, with Security, and a sense of insecurity), I was confronted with an evocative and representative situation, proving 1) that I was in fact home, and 2) that nothing is too trivial for me to discuss it here on Think Denk. A little backstory: I slept heavily through my entire cross-country flight, emerging into the terminal at a rather advanced point of the day without having consumed a drop of coffee. Au Bon Pain, near my gate, seemed like a good place to rectify this urgent situation, and I placed myself in line. However, there was a small quandary, as shown in the diagram below:

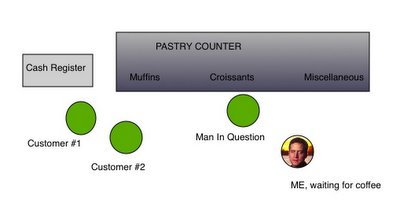

Two persons were clearly and umambiguously in line for the cash register, as evidenced by their proximity, whereas a third man (labelled Man In Question), a rather nebbishy fellow in his late forties, stood rather farther away... I intuited that he was nonetheless probably "in line," and merely consumed with choosing a pastry, but the question remained open in my mind, and it seemed possible he might head over to the refrigerator, for instance, to get a sandwich, or some sushi, an action in the cruel Lord-of-the-Flies world of the airport concession stand that would certainly place him "out of line" and force him to begin again from scratch. Groggy and caffeine-starved though I was, I reminded myself of our common humanity, and gave him the benefit of the doubt ... and ... all would have been well ... EXCEPT that soon enough, pressure came to bear on this situation, in the form of some impatient youths:

They had in fact chosen sandwiches from the refrigerator and were now coming to consummate their choices with a purchase. However, in the meantime, as the diagram shows, the nebbish in question had moved even a bit farther away from the invisible vector of the line, in order apparently to peer at more remote croissants. I still assumed that he represented the "end of the line," despite this renegade behavior, but the youths to my rear, in leather jackets, chafing at their fashionable bits, saw the huge gap between Customer #2 and the Man In Question and began to move past me... asking in the meantime "are you in line?" in a very dismissive way, like an unnecessary formality. It seemed too cruel for me to lose my spot in this fashion, and indefinitely postpone my cup of coffee at the whim of these youths, and I felt my hand was forced, and perhaps a bit overforcefully I said to the Man in Question, "Excuse me sir are you in line?" and at that moment he turned his head away from the croissants and gave me a pained expression I shall never forget. It seemed to distill a lifetime of being hassled and to convey a deep consciousness of the inexplicable impatience of the human sphere, within which we are all yoked. Yes: I, I, was the focus of this terrible, baleful, look, like that of an animal you have just fatally shot, and for a moment everything went still and the airport grew dim and the sun went behind the moon and time itself seemed to pause for my punishment:

"That's a real good question. Yes, I'm in line, and in another way I guess no, I'm looking and deciding; a little bit of both; is that OK with you?; does that mean I'm not still in line? If you have to, just go ahead, go ahead, do whatever you want, please just go on ahead, don't worry about me... whatever you want..."

So bitter, and so beautifully executed. A man who cut ahead at this point, as he was inviting me to do, would be ravaged by guilt, pursued by a croissant curse, for the remainder of his days; it was a passive-aggressive masterpiece. Somewhere in the cosmos there was silent, respectful applause. I looked helplessly at the youths who now also paused, and fell back into place behind me; I could not now shift the blame onto them, though of course I was caught between the generations, my 35-year-old impatient self harrassing the next older generation at the behest of the younger, by fateful proxy, against my will. It was so archetypal! Oh, the humanity!

I promise at some point some future post may actually discuss music again.

From the very first SECONDS of rearriving in the Homeland (a word now inextricably linked, sadly, with Security, and a sense of insecurity), I was confronted with an evocative and representative situation, proving 1) that I was in fact home, and 2) that nothing is too trivial for me to discuss it here on Think Denk. A little backstory: I slept heavily through my entire cross-country flight, emerging into the terminal at a rather advanced point of the day without having consumed a drop of coffee. Au Bon Pain, near my gate, seemed like a good place to rectify this urgent situation, and I placed myself in line. However, there was a small quandary, as shown in the diagram below:

Two persons were clearly and umambiguously in line for the cash register, as evidenced by their proximity, whereas a third man (labelled Man In Question), a rather nebbishy fellow in his late forties, stood rather farther away... I intuited that he was nonetheless probably "in line," and merely consumed with choosing a pastry, but the question remained open in my mind, and it seemed possible he might head over to the refrigerator, for instance, to get a sandwich, or some sushi, an action in the cruel Lord-of-the-Flies world of the airport concession stand that would certainly place him "out of line" and force him to begin again from scratch. Groggy and caffeine-starved though I was, I reminded myself of our common humanity, and gave him the benefit of the doubt ... and ... all would have been well ... EXCEPT that soon enough, pressure came to bear on this situation, in the form of some impatient youths:

They had in fact chosen sandwiches from the refrigerator and were now coming to consummate their choices with a purchase. However, in the meantime, as the diagram shows, the nebbish in question had moved even a bit farther away from the invisible vector of the line, in order apparently to peer at more remote croissants. I still assumed that he represented the "end of the line," despite this renegade behavior, but the youths to my rear, in leather jackets, chafing at their fashionable bits, saw the huge gap between Customer #2 and the Man In Question and began to move past me... asking in the meantime "are you in line?" in a very dismissive way, like an unnecessary formality. It seemed too cruel for me to lose my spot in this fashion, and indefinitely postpone my cup of coffee at the whim of these youths, and I felt my hand was forced, and perhaps a bit overforcefully I said to the Man in Question, "Excuse me sir are you in line?" and at that moment he turned his head away from the croissants and gave me a pained expression I shall never forget. It seemed to distill a lifetime of being hassled and to convey a deep consciousness of the inexplicable impatience of the human sphere, within which we are all yoked. Yes: I, I, was the focus of this terrible, baleful, look, like that of an animal you have just fatally shot, and for a moment everything went still and the airport grew dim and the sun went behind the moon and time itself seemed to pause for my punishment:

"That's a real good question. Yes, I'm in line, and in another way I guess no, I'm looking and deciding; a little bit of both; is that OK with you?; does that mean I'm not still in line? If you have to, just go ahead, go ahead, do whatever you want, please just go on ahead, don't worry about me... whatever you want..."

So bitter, and so beautifully executed. A man who cut ahead at this point, as he was inviting me to do, would be ravaged by guilt, pursued by a croissant curse, for the remainder of his days; it was a passive-aggressive masterpiece. Somewhere in the cosmos there was silent, respectful applause. I looked helplessly at the youths who now also paused, and fell back into place behind me; I could not now shift the blame onto them, though of course I was caught between the generations, my 35-year-old impatient self harrassing the next older generation at the behest of the younger, by fateful proxy, against my will. It was so archetypal! Oh, the humanity!

I promise at some point some future post may actually discuss music again.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Threats

When the driver handed us a business card, I was surprised to read, in boldface, "Threat Assessment." My dubious naïveté felt punctured, like a flat tire on the road to Vegas. Perhaps in the post-9/11 world, I was too complacent. All around me anti-pianist threats lurked, on the way from airport to hotel to hall, and thank goodness some strongman was there to assess them. For example, when i ordered a $14 entree in my hotel room, I found when the bill arrived that the total, with accompanying fees, was $35! Spectacular, devilish ingenuity of the Room Service Gods. The driver oddly did not save me from that pitfall (perhaps too busy assessing others), but he "reassured" me further on the way to the concert, boasting he was more than ready to break an arm or two (it "would not be the first time," he hinted), and reenacting a sarcastic conversation he might have with some hypothetical difficult concertgoer: "Oh I'm SO SORRY your shoulder got dislocated, now get out of here." I kid you not. I laughed what I hoped was a mollifying laugh and secretly cherished my fear and horror. Then a different laugh overtook me as I suddenly imagined some of the gentler Northeast presenters, in Philadelphia, or Boston, or a lovely, deeply cultured Italian lady running a small, modest, but serious series down in Washington DC--imagining any of them threatening to break arms as they drove me from the train station. Was it so much safer there than in the wild West? And what a strange preparation for the first, gentle, beatific phrase of Mozart's K 301...

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Chameleon

It is not always so easy to "be oneself." Looking back at various comments on this blog, I see scattered suggestions for me to be true to myself, which causes me undue anxiety; I wrack my brain, soul, stomach to find what I was when I was I. Am I, was I, not really myself for that short period? And why? I am now touring with Joshua Bell; we get up every night on a stage to project maybe three different selves: the identity of the music (hopefully first), and each of our respective identities, our thoughts in relation to the music, and maybe one could talk about a fourth--the identity of our intertwining dialogue. Josh's persona is quite strong; I find myself by turns dissolving into his playing and thinking, and then crystallizing back into my own self, trying to find the razor's edge, the bridge, between these states: in chemistry terms, a solute on the edge of solution. Supersaturated.

It is disquieting to imagine our identity in flux, that we are not as stable a thing as we imagine (Barthes calls each of us a patchwork of interlacing codes)... Perhaps one of the consoling things about the icons of classical music: a composer's style gives the sense of a recurring, identifiable personality between all his different pieces: the preservation of the elusive human soul-fingerprint, despite variety, in sound. Brahms is Brahms, X is X, and when Josh and I sit down to play the Five Melodies of Prokofiev, from the very first sonorities I can "feel" Prokofiev's strange beautiful breath on my ear. I love how the first, lyrical phrase is followed by a ghostly echo (identity/loss of identity?) where the piano descends into the bass (melody/non-melody)... a kind of disquieting undertone belying the almost too-easy lyricism of the first idea--a love is expressed; beneath it some ulterior motive, some dark relationship. I am partial to this side of Prokofiev, the Prokofiev of complicated (not too obvious) irony and stream-of-consciousness fragments, of digression and fantasy; I have to say it is my favorite side of his "self"; he is a friend whom I like best in a particular mood. The more bitterly ironic Prokofiev I find too bitter, too in-my-face, too simply rejecting; the pounding piano ostinatos and marches are fun but do not speak to my soul; and when his tremendous lyricism is unlaced with irony I often find it saccharine. So here I have another razor's edge: my own relationship to Prokofiev, which is personal, part of my identity ... my own agenda! I also adore his piano playing, which seems to me mainly lyrical, fanciful, evanescent--courting arrhythmia, in opposition to the oppressively rhythmic manner in which his music is often executed. Sometimes I wish only Prokofiev were permitted to play Prokofiev.

The third of the Five Melodies begins with a kind of ecstatic climax (from where? why? how?)--already a bizarre notion, an unjustified, preemptive lightning bolt--and gradually dies down to a long, still, ethereal arc; then the climax returns but softer -- an echo, an aftershock. Perhaps the form could be expressed thus:

ClIMAX... dying... dying... dead (a beautiful, sensual death) ... climax? (awake from dead? life remembered from death?)... disturbing, grinding coda...

Usually the "bigger" version of an idea would be towards the end--logically, progressively--but Prokofiev reverses this typical pattern, subtly using echo and disintegration (rather than development and ascension) as his formal motivations. Ahh, like a sinking feeling, some loss of meaning, some weird, falling, changing perspective. These asymmetries and peculiarities, these reversals of rhetoric, with the questions of tone and meaning they pose, cause me to connect these little five pieces to modernist verse, with the ambiguous alchemy of their bare-minimum words. It is not hard to move from the opening bars of the Five Melodies, for instance, to the following lines...

Let us go then, you and I

while the evening is spread out against the sky

like a patient etherized upon a table.

As Hugh Kenner points out in his wonderful book The Pound Era, the first two lines falsely promise a kind of Romantic outlook, a "conventional" love poem, while the third line deliciously delivers nonsense, antithesis, irony, the infusion of the modern, medicinal, procedural... the most un-Romantic simile imaginable. What kind of poem is it? Who is speaking? How can those lines possibly belong together? In other words, the questioning and challenging of identity, of the consistency of the self of the poem ... to what is the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock true? ... the beauty of the shifting self, of the moment of uncertainty, of the impossibility of fixing anything in place ... and yet, behind that flux, there is a new once-removed identity, the observer self looking at, following, his own complicated changing states, savoring, knowing, dissolving.

The maid left some smooth jazz on in my hotel room here in Arizona--a pure strange accident--and while I check emails my head is bopping, it seems to make me happy. Again a crisis of self. Am I really the kind of person who can enjoy smooth jazz? And then, is it possible for me, tonight, to play the "Kreutzer" Sonata? Arizonans will know soon enough.

It is disquieting to imagine our identity in flux, that we are not as stable a thing as we imagine (Barthes calls each of us a patchwork of interlacing codes)... Perhaps one of the consoling things about the icons of classical music: a composer's style gives the sense of a recurring, identifiable personality between all his different pieces: the preservation of the elusive human soul-fingerprint, despite variety, in sound. Brahms is Brahms, X is X, and when Josh and I sit down to play the Five Melodies of Prokofiev, from the very first sonorities I can "feel" Prokofiev's strange beautiful breath on my ear. I love how the first, lyrical phrase is followed by a ghostly echo (identity/loss of identity?) where the piano descends into the bass (melody/non-melody)... a kind of disquieting undertone belying the almost too-easy lyricism of the first idea--a love is expressed; beneath it some ulterior motive, some dark relationship. I am partial to this side of Prokofiev, the Prokofiev of complicated (not too obvious) irony and stream-of-consciousness fragments, of digression and fantasy; I have to say it is my favorite side of his "self"; he is a friend whom I like best in a particular mood. The more bitterly ironic Prokofiev I find too bitter, too in-my-face, too simply rejecting; the pounding piano ostinatos and marches are fun but do not speak to my soul; and when his tremendous lyricism is unlaced with irony I often find it saccharine. So here I have another razor's edge: my own relationship to Prokofiev, which is personal, part of my identity ... my own agenda! I also adore his piano playing, which seems to me mainly lyrical, fanciful, evanescent--courting arrhythmia, in opposition to the oppressively rhythmic manner in which his music is often executed. Sometimes I wish only Prokofiev were permitted to play Prokofiev.

The third of the Five Melodies begins with a kind of ecstatic climax (from where? why? how?)--already a bizarre notion, an unjustified, preemptive lightning bolt--and gradually dies down to a long, still, ethereal arc; then the climax returns but softer -- an echo, an aftershock. Perhaps the form could be expressed thus:

ClIMAX... dying... dying... dead (a beautiful, sensual death) ... climax? (awake from dead? life remembered from death?)... disturbing, grinding coda...

Usually the "bigger" version of an idea would be towards the end--logically, progressively--but Prokofiev reverses this typical pattern, subtly using echo and disintegration (rather than development and ascension) as his formal motivations. Ahh, like a sinking feeling, some loss of meaning, some weird, falling, changing perspective. These asymmetries and peculiarities, these reversals of rhetoric, with the questions of tone and meaning they pose, cause me to connect these little five pieces to modernist verse, with the ambiguous alchemy of their bare-minimum words. It is not hard to move from the opening bars of the Five Melodies, for instance, to the following lines...

Let us go then, you and I

while the evening is spread out against the sky

like a patient etherized upon a table.

As Hugh Kenner points out in his wonderful book The Pound Era, the first two lines falsely promise a kind of Romantic outlook, a "conventional" love poem, while the third line deliciously delivers nonsense, antithesis, irony, the infusion of the modern, medicinal, procedural... the most un-Romantic simile imaginable. What kind of poem is it? Who is speaking? How can those lines possibly belong together? In other words, the questioning and challenging of identity, of the consistency of the self of the poem ... to what is the Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock true? ... the beauty of the shifting self, of the moment of uncertainty, of the impossibility of fixing anything in place ... and yet, behind that flux, there is a new once-removed identity, the observer self looking at, following, his own complicated changing states, savoring, knowing, dissolving.

The maid left some smooth jazz on in my hotel room here in Arizona--a pure strange accident--and while I check emails my head is bopping, it seems to make me happy. Again a crisis of self. Am I really the kind of person who can enjoy smooth jazz? And then, is it possible for me, tonight, to play the "Kreutzer" Sonata? Arizonans will know soon enough.

Friday, February 10, 2006

Wisdom

Cabbie: Where to?

Me: Symphony Hall, please.

[pulls away from my hotel, turns right, begins to careen down Powell Street]

Cabbie: So, you a musician?

Me: You got me.

Cabbie: I knew it. What do you play?

Me: Piano.

Cabbie: I bet you know your middle C pretty well.

Me: [attempting wit] C is pretty solid. Still working on D and E...

Cabbie: And those thumbcrossings. Eh.

[Ensuing pantomime of a thumbcrossing--possibly a major scale. One or both hands leaves the wheel. He looks back to smile at me. Car in front of us stops suddenly. Dumbstruck me. Somehow he notices in time, abandons scale, swerves, brakes. Near-death. We survive. Diminishing panic. Other driver is accused of stopping "too late." Drive resumes.]

Cabbie: So. I had piano lessons.

Me: Is that so?

Cabbie: Yeah. The teacher told me "no, you're not doing that thumbcrossing right," and I told her go to hell, I'm going to play football.

[I silently reflect this is the shortest piano lesson story I have ever been told, and perhaps the best. This man probably speaks for piano students everywhere.]

Me: You ever regret not sticking with it?

Cabbie: [Conspicuously unregretful in tone] Yeah, all the time. You know San Francisco at all?

Me: A little.

Cabbie: Well, there used to be this piano shop round here which my friend owned, and it connected to a deli. You could walk right through from one to the other! You know, piano salesmen are like used car guys, with all the extra charges, and the one-more-things. Anyway, I worked the deli for a little while, to help my friend out cause of some trouble ... that's another story ... and so one day I was working and the shop was about to close, it was ten to six and we closed at six, and the Opera called, and they wanted some sandwiches!

Me: OK.

Cabbie: And so these two women came in, and I was still making their food, and the one, her accompanist, walked into the piano shop, and the other one asked me if I minded if she sang, and what am I gonna say? I don't want a free concert?! So they sang, and it was amazing. Beautiful. Really good.

Me: Nice.

Cabbie: So I fell in love with her.

Me: Really?

Cabbie: It's true I did. And you know I took her out and you know...

Me: Really?

Cabbie: Yeah and this went on for like a week or so. I sent her flowers and all that crap.

Me: Hmm.

Cabbie: Then one day she was like, you know I have this dilemma, there's this guy in Sacramento and he's very close to being my fiancee and I just don't know what to do. And after that I never heard from her again.

[Silence. Very close to the hall now.]

Me: [Stammering] I'm sorry.

Cabbie: No no, it was a great experience, you know.

Me: Yeah. Can I pay with a credit card?

Me: Symphony Hall, please.

[pulls away from my hotel, turns right, begins to careen down Powell Street]

Cabbie: So, you a musician?

Me: You got me.

Cabbie: I knew it. What do you play?

Me: Piano.

Cabbie: I bet you know your middle C pretty well.

Me: [attempting wit] C is pretty solid. Still working on D and E...

Cabbie: And those thumbcrossings. Eh.

[Ensuing pantomime of a thumbcrossing--possibly a major scale. One or both hands leaves the wheel. He looks back to smile at me. Car in front of us stops suddenly. Dumbstruck me. Somehow he notices in time, abandons scale, swerves, brakes. Near-death. We survive. Diminishing panic. Other driver is accused of stopping "too late." Drive resumes.]

Cabbie: So. I had piano lessons.

Me: Is that so?

Cabbie: Yeah. The teacher told me "no, you're not doing that thumbcrossing right," and I told her go to hell, I'm going to play football.

[I silently reflect this is the shortest piano lesson story I have ever been told, and perhaps the best. This man probably speaks for piano students everywhere.]

Me: You ever regret not sticking with it?

Cabbie: [Conspicuously unregretful in tone] Yeah, all the time. You know San Francisco at all?

Me: A little.

Cabbie: Well, there used to be this piano shop round here which my friend owned, and it connected to a deli. You could walk right through from one to the other! You know, piano salesmen are like used car guys, with all the extra charges, and the one-more-things. Anyway, I worked the deli for a little while, to help my friend out cause of some trouble ... that's another story ... and so one day I was working and the shop was about to close, it was ten to six and we closed at six, and the Opera called, and they wanted some sandwiches!

Me: OK.

Cabbie: And so these two women came in, and I was still making their food, and the one, her accompanist, walked into the piano shop, and the other one asked me if I minded if she sang, and what am I gonna say? I don't want a free concert?! So they sang, and it was amazing. Beautiful. Really good.

Me: Nice.

Cabbie: So I fell in love with her.

Me: Really?

Cabbie: It's true I did. And you know I took her out and you know...

Me: Really?

Cabbie: Yeah and this went on for like a week or so. I sent her flowers and all that crap.

Me: Hmm.

Cabbie: Then one day she was like, you know I have this dilemma, there's this guy in Sacramento and he's very close to being my fiancee and I just don't know what to do. And after that I never heard from her again.

[Silence. Very close to the hall now.]

Me: [Stammering] I'm sorry.

Cabbie: No no, it was a great experience, you know.

Me: Yeah. Can I pay with a credit card?

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Early Flight

The first events of the day were a vague beeping and a dream of boiling clouds. The clouds scattered, the beeping grew more present, and like a tribal signal I began to understand with horror what sacrifice it demanded of me. Shortly thereafter I found myself wandering around the room, vaguely disembodied, halting, like an outdated packing robot. I was leaning over to put on my socks when a man in charge of a fleet of black four-door sedans took pity on me. I could hear soft sympathy in his dispatching tone, though I was late for my pickup. "How are you feeling this morning, Sir?" I tried to sound brave, nonchalant, optimistic. Why did I not want him to lose confidence in me as a customer? Never mind my three hours' sleep, I was thrilled to hit the airport, and I would be dashing out the door of my building with my bags any second, all smiles, giggles, and existential bliss. A small list of things-to-do-before-I-leave bubbled through my brain and threatened to leak out all over the floor, and I kept cramming them back in, like items in a suitcase, through mantric repetition, which made me feel kind of desperate or insane, like the insomniacs in One Hundred Years of Solitude who label everything around them as lack of sleep erodes their sense of language. For some reason in the midst of the madness I picked up "Awakenings" (by Oliver Sacks) and read a paragraph about a woman who dreamed she was imprisoned in a castle, which was herself.

And now the glow over the industrial, rusty wastes of Queens is really quite beautiful, especially from the comfort of a backseat. If I were out there in the cold hard world, lugging luggage from train to bus to train, I may not have had quite the impulse or occasion to savor this super-orange curtain rising from a side of the sky. After the first five minutes in the cab or car, five minutes of residual panic where you go over all the possible things you have forgotten (music--always music first!--wallet, keys, credit card, driver's license, joie de vivre, itinerary, etc.), then there is a delicious surrender. The vehicle, motion itself, takes you; it is generally sad but pleasant; there is either traffic which is its own pattern of starts and stops, or there is the empty sleepy city, with all the faintly glowing apartments of peaceful and warlike people with their distant unknowable lives; and you float or inch alone in your bubble towards another bubble which will carry you across continents or oceans ... as I said, it is generally sad, a time for musing, for seeing what's past and done, for remembering all the previous trips, all the old, dilapidated Triboro bridges of your life to date, the motivations (loves, desires, needs) which carried you all these places, many forgotten; I look out the window and wallow in this slightly ridiculous mood, such that I am always surprised by the practicality of dealing with the driver at the destination. The cold, present airport curb, where accumulated, hoarded memory makes way for anonymous transit.

And now, through security: the strange light of the coffee kiosk. A line of fifteen people or more awaits, and I glare from afar at the barista. Even if he were some outrageous, wonderful monster of coffee-serving efficiency, some super-human grinder/brewer who wasted not one millimeter of motion or iota of thought in preparing our beverages, it would still not be enough; coffee means to resent the postponement of coffee. A woman, perversely, decides to try to find exact coins for her purchase; she ransacks her change purse; pennies are long sought, dropped, re-found; I have never seen such an outrage; I seethe. Woman, can you not see the inhumanity of what you are doing?

Calm down, gentle soul. Soon you will be on the plane and off to the West Coast; visions of dim sum, spas, espresso, blue waters... of people who have prioritized the pure pleasure of life, and not distilled action. I will stare lovingly at their pierced lips, torn jeans, and half-hidden tattoos, and envy an imaginary, unwanted freedom. As I gave my boarding pass to the lady at the gate, I thought I asked her if I was boarding at the right time. Did she hear me? I think she did, but she probed deeper and saw behind my eyes an early morning mania, that slightly more dangerous question posed by the three-hour sleeper with last night's ginger chicken undigested in the premature morning. And she chose to address that deeper question instead: "Everything's okay so far," she said--a broader, diagnostic answer--oddly echoing the dispatcher's earlier solicitude. I did find myself enjoying her smile as I went down the jetbridge, taking disproportionate comfort ... I was happier and more grounded now that she had welcomed me onto the plane; but what did she mean by "so far"? That, I suppose, was all she could promise.

It was contingent, but from the car service which was a bubble of the past, mulled over in orange, I find myself transported to a room with sunny windows, and a view of the blue water I had hoped for, and expensive bottled water (clear, blue, light); a room which feels like the present, which opens onto a promising outdoors; only unpacking now needs to be done; no going, only being; for which I need no saintly dispatcher or ticket-taker, no reassurance.

And now the glow over the industrial, rusty wastes of Queens is really quite beautiful, especially from the comfort of a backseat. If I were out there in the cold hard world, lugging luggage from train to bus to train, I may not have had quite the impulse or occasion to savor this super-orange curtain rising from a side of the sky. After the first five minutes in the cab or car, five minutes of residual panic where you go over all the possible things you have forgotten (music--always music first!--wallet, keys, credit card, driver's license, joie de vivre, itinerary, etc.), then there is a delicious surrender. The vehicle, motion itself, takes you; it is generally sad but pleasant; there is either traffic which is its own pattern of starts and stops, or there is the empty sleepy city, with all the faintly glowing apartments of peaceful and warlike people with their distant unknowable lives; and you float or inch alone in your bubble towards another bubble which will carry you across continents or oceans ... as I said, it is generally sad, a time for musing, for seeing what's past and done, for remembering all the previous trips, all the old, dilapidated Triboro bridges of your life to date, the motivations (loves, desires, needs) which carried you all these places, many forgotten; I look out the window and wallow in this slightly ridiculous mood, such that I am always surprised by the practicality of dealing with the driver at the destination. The cold, present airport curb, where accumulated, hoarded memory makes way for anonymous transit.

And now, through security: the strange light of the coffee kiosk. A line of fifteen people or more awaits, and I glare from afar at the barista. Even if he were some outrageous, wonderful monster of coffee-serving efficiency, some super-human grinder/brewer who wasted not one millimeter of motion or iota of thought in preparing our beverages, it would still not be enough; coffee means to resent the postponement of coffee. A woman, perversely, decides to try to find exact coins for her purchase; she ransacks her change purse; pennies are long sought, dropped, re-found; I have never seen such an outrage; I seethe. Woman, can you not see the inhumanity of what you are doing?

Calm down, gentle soul. Soon you will be on the plane and off to the West Coast; visions of dim sum, spas, espresso, blue waters... of people who have prioritized the pure pleasure of life, and not distilled action. I will stare lovingly at their pierced lips, torn jeans, and half-hidden tattoos, and envy an imaginary, unwanted freedom. As I gave my boarding pass to the lady at the gate, I thought I asked her if I was boarding at the right time. Did she hear me? I think she did, but she probed deeper and saw behind my eyes an early morning mania, that slightly more dangerous question posed by the three-hour sleeper with last night's ginger chicken undigested in the premature morning. And she chose to address that deeper question instead: "Everything's okay so far," she said--a broader, diagnostic answer--oddly echoing the dispatcher's earlier solicitude. I did find myself enjoying her smile as I went down the jetbridge, taking disproportionate comfort ... I was happier and more grounded now that she had welcomed me onto the plane; but what did she mean by "so far"? That, I suppose, was all she could promise.

It was contingent, but from the car service which was a bubble of the past, mulled over in orange, I find myself transported to a room with sunny windows, and a view of the blue water I had hoped for, and expensive bottled water (clear, blue, light); a room which feels like the present, which opens onto a promising outdoors; only unpacking now needs to be done; no going, only being; for which I need no saintly dispatcher or ticket-taker, no reassurance.

Thursday, January 26, 2006

WOW!

I have noticed a slight uptick in the irritability of the universe lately. My evidence? The other day, I was in Starbucks minding my own business (so all these stories begin), typing nonsense at my too-cool-for-school laptop, when I noticed a man set something down at the empty adjoining table. Perhaps a minute later, another man put something at another spot by the same table. Both left to get in line, and both, sadly, came to the table with their drinks simultaneously, intending to sit and occupy (veni, vidi, vici): a childish spat ensued. I couldn't believe how stubborn each was to the cause, which was, after all, just a table (or perhaps more: a moment of repose?). The dispute ended by "sharing"; they each refused to relinquish, and sat the same table, glowering, sucking up each other's negative energy. One was in his early 20s, impeccably dressed, indubitably gay, and somewhat on the sniffy side of the spectrum; the other probably early 60s, peccably dressed, squarely straight, far on the grumpy side of the spectrum (almost invisible to the genial eye), and reading--of course--the NY Post. A mini culture war for my benefit. The younger one talked loudly on his cellphone to irritate his table mate, while the older read his Post, crinkling and uncrinkling, folding and refolding: a motion like the flapping wings of a giant, tired, grimy bat. Needless to say, I was quite irritated and distracted by this tempest in a teapot, perhaps even enraged, and eventually got up, pulled my handy chainsaw out of its case, and made a clean slice...

Just kidding.

I also witnessed this morning a similar dispute between a burly construction worker from Long Island and a small elderly Jewish lady, in Tal Bagels, revolving around the eternal issue of "where the line begins." (If only we could always know!) Luckily this dispute did not come to blows; I feel sure she would have embarrassed him rather badly.

These, along with several other instances of New Yorker irritability, have made me sense the vague winds of a trend... And this trend has even carried over into this very blog (heavens!) since my snarky post "BS of the day," in which I took a Mr. Wilson to task for some vague comments about Mozart, inspired quite a few reactions, and even the unimaginable: criticisms. I suppose this is to be seen not as a sad outcome, or even as a loss of innocence (a de-virginization of the blog) but as a positive thing, an act of birth, even: something has engendered a "discussion."

Let me just say a few more things toward this discussion, to try and mend some fences.

1) "BS of the day" was a self-conscious attempt to imitate other, snarky blogs such as Wonkette. I do not intend to adopt this style permanently, and I apologize to those readers who felt offended. Occasionally is it OK, though, if I just rant about something? Thanks.

2) I think opera is fantastic.

3) I was disheartened by the disintegration of the discourse into (sigh, as usual) a maligning of analysis. This happens so easily! I saw it in one of the comments: it began with the coupling of the words "erudite" and "analysis," which makes it seem a bit elitist already; and then, sure enough, the word "dissection" made its way in there; and then "there's no pleasure left." People say "you are analyzing this to death!" as if discussion and contemplation of music were some sort of murderous activity, some sort of science-lab experiment in which a frog must die, pinned to the table.

I have my own gripes with analysis, believe me. But I don't think the answer is this kind of dismissal, this kind of easy getaway, as in: what's the point of analysis anyway? followed by "meet you at the Redeye Grill for martinis." Specifically to keep my vision fresh, I feel the need to keep asking the same unanswerable questions about the music I am playing over and over again, to reach into verbal language for what it has to offer and cross back into the language of tones like a returning tourist. I feel this is similar to when I sing a phrase to myself in my head, when I imagine the music without sound (or at least anything that anyone else could hear); things are almost always better back at the piano--wider, freer--after this kind of removal, the removal of music from sound, its temporary passage into gesture, thought, imagination. If you are still thinking about martinis, I don't blame you.

I spent a great deal of time on Op. 111 this week, verbally and mentally, thinking how to communicate something about it to 25 freshmen. Of course I think the happiest, most enlightened person after the hour-and-a-half lecture was me. For the umpteenth time I felt I "finally" knew what I wanted to say (notice how we use that phrase as a compliment: "his playing really SAYS something to me, really SPEAKS to me"--even for non-verbal music!) with this piece, and the next day on the train back down the Hudson, this happiness became more pronounced. Scarfing my stir-fry in Penn Station, amidst a hassled underground crowd, I was singing inaudibly over and over again thirds, fourths, fifths from the Arietta. Well, perhaps not inaudibly; in my blissful imagined solitude, I might have moaned a little, enough so that the man who had cooked up my stirfry looked up and asked "It tastes good?" He looked either amused or concerned; food in that place wasn't really meant to be "enjoyed;" I smiled like a good little deranged maniac and said yes, it was delicious; he really didn't need to know the truth.

How was it that magic dust had been sprinkled again all over that theme, in that ugly place? Maybe it was partly the article that my colleague had xeroxed for me, in which I read that Schenker (a hardcore theorist if there ever was one) broke off from the world of technical terms and called the cadenza of the Arietta a "strange dream;" maybe it was the little technical/emotional phrase in the article "vertiginous fall of fifths" which showed me a pattern I had been too lazy to notice, while feeling all the while something frightening about that place--that it was too much to absorb, that everything was slipping away, that it was gravity-free, like the sense of (infinitely, impossibly) falling in a dream; maybe it was the part in which Schenker talks about the one high F which means so much to him, at a moment when the movement leaves off, loses track of itself, in which its ecstasy is so extreme that it cannot possibly continue along the path it is taking; and maybe it was partly a phone conversation with my friend C who said he was struck again, freshly, how in the wild, syncopated variation Beethoven seemed to see, ahead of time, the joyfulness of jazz, to anticipate so amazingly things which are now part of our lives, and C's use of the word "joyful" which is probably the perfect word to define on what side of an invisible fence the movement's austerity and transcendence lies.

How is that these little "academic thoughts" managed to whip me up into a frenzy of enjoying the movement all over again? It was not analyzed to death; it was analyzed to life. Only the three notes, long-short-long: just that, and the path leads off into a labyrinth in which the means of escape is never twice the same, in which the focal moments can change according to the observer or the day... Each time to play it: like entering/creating a universe. There is always the moment of being "too full," the sense that the adventure has reached a crisis point, that the emotion or invention has gone so far that you or the piano will explode; and always the balancing moment where things are slipping away, and dangerously "empty;" and always the starry conclusion, resolving or disappearing, twinkling with the high frequencies of the piano, promising, always promising...

Just kidding.

I also witnessed this morning a similar dispute between a burly construction worker from Long Island and a small elderly Jewish lady, in Tal Bagels, revolving around the eternal issue of "where the line begins." (If only we could always know!) Luckily this dispute did not come to blows; I feel sure she would have embarrassed him rather badly.

These, along with several other instances of New Yorker irritability, have made me sense the vague winds of a trend... And this trend has even carried over into this very blog (heavens!) since my snarky post "BS of the day," in which I took a Mr. Wilson to task for some vague comments about Mozart, inspired quite a few reactions, and even the unimaginable: criticisms. I suppose this is to be seen not as a sad outcome, or even as a loss of innocence (a de-virginization of the blog) but as a positive thing, an act of birth, even: something has engendered a "discussion."

Let me just say a few more things toward this discussion, to try and mend some fences.

1) "BS of the day" was a self-conscious attempt to imitate other, snarky blogs such as Wonkette. I do not intend to adopt this style permanently, and I apologize to those readers who felt offended. Occasionally is it OK, though, if I just rant about something? Thanks.

2) I think opera is fantastic.

3) I was disheartened by the disintegration of the discourse into (sigh, as usual) a maligning of analysis. This happens so easily! I saw it in one of the comments: it began with the coupling of the words "erudite" and "analysis," which makes it seem a bit elitist already; and then, sure enough, the word "dissection" made its way in there; and then "there's no pleasure left." People say "you are analyzing this to death!" as if discussion and contemplation of music were some sort of murderous activity, some sort of science-lab experiment in which a frog must die, pinned to the table.

I have my own gripes with analysis, believe me. But I don't think the answer is this kind of dismissal, this kind of easy getaway, as in: what's the point of analysis anyway? followed by "meet you at the Redeye Grill for martinis." Specifically to keep my vision fresh, I feel the need to keep asking the same unanswerable questions about the music I am playing over and over again, to reach into verbal language for what it has to offer and cross back into the language of tones like a returning tourist. I feel this is similar to when I sing a phrase to myself in my head, when I imagine the music without sound (or at least anything that anyone else could hear); things are almost always better back at the piano--wider, freer--after this kind of removal, the removal of music from sound, its temporary passage into gesture, thought, imagination. If you are still thinking about martinis, I don't blame you.

I spent a great deal of time on Op. 111 this week, verbally and mentally, thinking how to communicate something about it to 25 freshmen. Of course I think the happiest, most enlightened person after the hour-and-a-half lecture was me. For the umpteenth time I felt I "finally" knew what I wanted to say (notice how we use that phrase as a compliment: "his playing really SAYS something to me, really SPEAKS to me"--even for non-verbal music!) with this piece, and the next day on the train back down the Hudson, this happiness became more pronounced. Scarfing my stir-fry in Penn Station, amidst a hassled underground crowd, I was singing inaudibly over and over again thirds, fourths, fifths from the Arietta. Well, perhaps not inaudibly; in my blissful imagined solitude, I might have moaned a little, enough so that the man who had cooked up my stirfry looked up and asked "It tastes good?" He looked either amused or concerned; food in that place wasn't really meant to be "enjoyed;" I smiled like a good little deranged maniac and said yes, it was delicious; he really didn't need to know the truth.

How was it that magic dust had been sprinkled again all over that theme, in that ugly place? Maybe it was partly the article that my colleague had xeroxed for me, in which I read that Schenker (a hardcore theorist if there ever was one) broke off from the world of technical terms and called the cadenza of the Arietta a "strange dream;" maybe it was the little technical/emotional phrase in the article "vertiginous fall of fifths" which showed me a pattern I had been too lazy to notice, while feeling all the while something frightening about that place--that it was too much to absorb, that everything was slipping away, that it was gravity-free, like the sense of (infinitely, impossibly) falling in a dream; maybe it was the part in which Schenker talks about the one high F which means so much to him, at a moment when the movement leaves off, loses track of itself, in which its ecstasy is so extreme that it cannot possibly continue along the path it is taking; and maybe it was partly a phone conversation with my friend C who said he was struck again, freshly, how in the wild, syncopated variation Beethoven seemed to see, ahead of time, the joyfulness of jazz, to anticipate so amazingly things which are now part of our lives, and C's use of the word "joyful" which is probably the perfect word to define on what side of an invisible fence the movement's austerity and transcendence lies.

How is that these little "academic thoughts" managed to whip me up into a frenzy of enjoying the movement all over again? It was not analyzed to death; it was analyzed to life. Only the three notes, long-short-long: just that, and the path leads off into a labyrinth in which the means of escape is never twice the same, in which the focal moments can change according to the observer or the day... Each time to play it: like entering/creating a universe. There is always the moment of being "too full," the sense that the adventure has reached a crisis point, that the emotion or invention has gone so far that you or the piano will explode; and always the balancing moment where things are slipping away, and dangerously "empty;" and always the starry conclusion, resolving or disappearing, twinkling with the high frequencies of the piano, promising, always promising...

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

Cheating

"The close of the Arietta variations has such a force of looking back, of leavetaking, that, as if over-illuminated by this departure, what has gone before is immeasurably enlarged. This despite the fact that the variations themselves, up to the symphonic conclusion of the last, contain scarcely a moment which could counterbalance that of leavetaking as fulfilled present--and such a moment may well be denied to music, which exists in illusion. But the true power of illusion in Beethoven's music--of the 'dream among eternal stars'--is that it can invoke what has not been as something past and non-existent. Utopia is heard only as what has already been. The music's inherent sense of form [emphasis added by blogger] changes what has preceded the leavetaking in such a way that it takes on a greatness, a presence in the past which, within music, it could never achieve in the present."

--Adorno, musing on Op. 111 Beethoven

and then:

Poetry

I

The agonizing question

whether inspiration is hot or cold

is not a matter of thermodynamics.

Raptus doesn't produce, the void doesn't conduce,

there's no poetry a la sorbet or barbecued.

It's more a matter of very

importunate words

rushing

from oven or deep freeze.